Category Archives: Disaster Risk Management

【Disaster Research: Infograph】AI-Integrated Disaster Preparedness Platforms (Open Access Examples)

The infographic of the AI-Integrated Disaster Preparedness Platforms is shown as an infographic: AI-Integrated Disaster Preparedness Platforms

【Disaster Research: Infograph】Global Trends of Disasters

The infographic of the global trends of disasters (1970-2025) is shown as an infographic: https://disasters.weblike.jp/global%20trends.html

【Disaster Research: Infograph】1985 mexico city earthquake

The infographic of the 1985 Mexico City Earthquake, mainly focusing on the social factors with earthquake characteristics, is shown as an infographic: http://disasters.weblike.jp/mexico%20infogr.html

The distance impact reminded me of the situation in Bangkok when an earthquake occurred in Myanmar in April 2025.

【Disaster Research: Infograph】The 2004 Tsunami in Thailand

This infographic was presented at RIHN in Japan as part of the Prof. Ito project, as part of the Feasibility Study. The infographic website is: https://disasters.weblike.jp/IOT%20v2.html

The presented numbers should be confirmed. Especially, the foreigner’s death toll and the Thai national death toll, with their proportion, are under reinvestigation.

【Disaster Research:Infograph】Myanmar’s Education Sector Impact & Recovery

An infographic, “Myanmar Earthquake 2025 Educational Sector Impact & Recovery Roadmap,” was created. Myanmar Earthquake 2025 Educational Sector Impact & Recovery Roadmap

*Please note that these are my research results, for my memo.

【Disaster Research】When Nature Meets Human Error: Lessons from History’s Deadliest Volcanic Mudflow 40 Years Ago

Growing up, many of us were taught that natural disasters are inevitable acts of nature beyond human control. This perspective changed dramatically for me when I started working at a research institute. My senior researcher emphatically told me, “The natural disaster is not natural.” This profound statement transformed my approach to disaster research, helping me understand that human decisions often determine whether natural hazards become catastrophic disasters.

The Forgotten Tragedy of Armero

On November 13, 1985, the Nevado del Ruiz volcano in Colombia erupted after 69 years of dormancy. The eruption triggered massive mudflows (lahars) that rushed down the volcano’s slopes, burying the town of Armero and claiming over 23,000 lives. This catastrophe stands as Colombia’s worst natural hazard-induced disaster and the deadliest lahar ever recorded.

What makes this tragedy particularly heartbreaking is its preventability. Scientists had observed warning signs for months, with seismic activity beginning as early as November 1984. By March 1985, a UN seismologist had observed a 150-meter vapor column erupting from the mountain and concluded that a major eruption was likely.

Despite these warnings, effective action to protect the vulnerable population never materialized. The devastation of Armero wasn’t simply the result of volcanic activity but the culmination of multiple human failures in risk communication, historical memory, and emergency response.

When Warning Systems Fail: Communication Breakdown

The Armero disaster epitomizes what disaster researchers call “cascading failures” in warning systems. Scientists had created hazard maps showing the potential danger to Armero in October 1985, just weeks before the eruption. However, these maps suffered from critical design flaws that rendered them ineffective.

One version lacked a clear legend to interpret the colored zones, making it incomprehensible to the general public. Devastatingly, Armero was placed within a green zone on some maps, which many residents misinterpreted as indicating safety rather than danger. According to reports, many survivors later recounted they had never even heard of the hazard maps before the eruption, despite their publication in several major newspapers.

As a disaster researcher, I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly: scientific knowledge fails to translate into public understanding and action. When I conducted fieldwork in flood-prone regions in Thailand, I discovered a similar disconnect between technical risk assessments and public perception. Effective disaster mitigation requires not just accurate information but information that is accessible and actionable for those at risk.

The Cultural Blindspots of Risk Perception

The tragedy of Armero illustrates how cultural and historical factors shape how communities perceive risk. Despite previous eruptions destroying the town in 1595 and 1845, causing approximately 636 and 1,000 deaths respectively, collective memory of these disasters had seemingly faded as the town was rebuilt in the same location.

In the hours before the disaster, when ash began falling around 3:00 PM, local leaders, including the town priest, reportedly advised people to “stay calm” and remain indoors. Some residents recall a priest encouraging them to “enjoy this beautiful show” of ashfall, suggesting it was harmless. These reassurances from trusted community figures likely discouraged self-evacuation that might have saved lives.

My research in disaster-prone communities has consistently shown that risk perception is heavily influenced by cultural factors, including trust in authority figures and historical experience with hazards. In Japan, for instance, the tsunami markers that indicate historic high-water levels serve as constant physical reminders of past disasters, helping to maintain community awareness across generations.

Systemic Failures and Institutional Response

The Armero tragedy wasn’t just a failure of risk communication or cultural blind spots—it revealed systemic weaknesses in disaster governance. Colombia was grappling with significant political instability due to years of civil war, potentially diverting governmental resources from disaster preparedness. Just a week before the eruption, the government was heavily focused on a guerrilla siege at the Palace of Justice in Bogotá.

Reports suggest there was reluctance on the part of the government to bear the potential economic and political repercussions of ordering an evacuation that might have proven unnecessary. This hesitation proved fatal when communication systems failed on the night of the eruption due to a severe storm, preventing warnings from reaching residents even after the lahars were already descending toward the town.

In my research examining large-scale flood disasters, I’ve found that effective disaster governance requires robust institutions that prioritize public safety over short-term economic or political considerations. My 2021 comparative analysis of major flood events demonstrated that preemptive protective actions consistently save more lives than reactive emergency responses, even when accounting for false alarms.

Learning from Tragedy: The Path Forward

The Armero disaster, while devastating, catalyzed significant advancements in volcano monitoring and disaster risk reduction globally. Colombia established specialized disaster management agencies with greater emphasis on proactive preparedness. The

Colombian Geological Service expanded from limited capacity to a network of 600 stations monitoring 23 active volcanoes.

The contrast with the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines demonstrates the impact of these lessons. There, timely forecasts and effective evacuation procedures saved thousands of lives. The memory of Armero remains a powerful reminder of the consequences of inadequate disaster preparedness.

As I’ve emphasized in my own research on disaster resilience in industrial complex areas, building sustainable communities requires integrating technical knowledge with social systems. My work developing social vulnerability indices demonstrates that effective disaster risk reduction must address both physical hazards and social vulnerabilities.

Remember, disasters may be triggered by natural events, but their impact is determined by human decisions. By learning from tragedies like Armero, we can create more resilient communities prepared to face future challenges.

【Disaster Research:Excel】Pivot Tables for Disaster Research: A Step-by-Step Guide

Today, I gonna explain how to use a pivot table to conduct disaster research using dummy data.

What is a Pivot Table?

Imagine you have a big pile of data, and you want to see summaries or patterns quickly. A pivot table lets you rearrange (or “pivot”) that data to show different views, like totals, averages, or counts, without changing the original data.

Sample Disaster Research Dataset:

dummy dataset

Step-by-Step Pivot Table Analysis for Disaster Research

- Select Data & Insert Pivot Table

- Select all the data (Ctrl+A or Cmd+A)

- Go to “Insert” → “PivotTable” → “OK” (for a new worksheet or you can choose the location in the same sheet)

- Total Aid Provided by Disaster Type

The sum of Aid by Disaster Type

- Drag “Disaster Type” to the “Rows” box

- Drag “Aid Provided (USD)” to the “Values” box (automatically shows sum of aid)

- Interpretation: Quickly identify which disaster types received the most total aid

- Aid Provided by Organization

- Remove “Disaster Type” from rows and add “Organization” instead

- Keep “Aid Provided (USD)” in the “Values” box

- Interpretation: Visualize which organizations have contributed the most aid overall

- Aid Provided by Year

- Replace “Organization” with “Year” in the “Rows” box

- Keep “Aid Provided (USD)” in the “Values” box

- Interpretation: Track annual patterns in aid disbursement over time

- Aid Provided by Disaster Type and Year

- Add “Disaster Type” to the “Rows” box

- Place “Year” in the “Columns” box

- Keep “Aid Provided (USD)” in the “Values” box

- Interpretation: Create a cross-tabulation showing aid distribution across disaster types and years

- Average Aid Provided

- Click on “Sum of Aid Provided (USD)” in the “Values” box

- Select “Value Field Settings” → “Average” → “OK”

- Interpretation: Compare the average aid amounts across categories

- Filtering by Location

- Add “Location” to the “Filters” box

- Use the dropdown to select a specific location (e.g., Nepal)

- Interpretation: Focus your analysis on specific geographic regions

- Counting Disaster Occurrences

Sorted Table

- Remove “Aid Provided (USD)” from values

- Add “Disaster Type” to the values box

- Change the value field setting from sum to count

- Interpretation: Track the frequency of different disaster types in your dataset

Key Insights from Disaster Research Pivot Tables

- Aid Distribution Analysis: Identify which disaster types or locations receive the most financial support

- Organizational Impact Assessment: Understand which relief organizations are most active in different scenarios

- Temporal Trend Identification: Analyze how aid distribution patterns change over months, quarters, or years

- Comparative Regional Analysis: Compare aid efforts across different geographic areas and disaster contexts

By experimenting with different field combinations, you can uncover valuable insights from your disaster research data. Pivot tables transform complex datasets into actionable intelligence for disaster management, policy development, and resource allocation.

Content Gap Opportunities

- A section on advanced pivot table features specifically useful for disaster research

- Guidance on data visualization options after creating pivot tables

- Information on combining pivot tables with other analytical tools for comprehensive disaster analysis

- Tips for presenting pivot table findings to non-technical stakeholders

【Disaster Research】Thailand Natural Disaster Risk Assessment: A Comprehensive Analysis (Revised)

Understanding Disaster Risk Profiles in Thailand

As highlighted in the Bangkok Post article, “More must be done to fight climate change“, Thailand faces significant challenges from various natural disasters. This analysis presents a national risk assessment mapping to help identify priority areas for disaster management.

Historical Disaster Impact Analysis

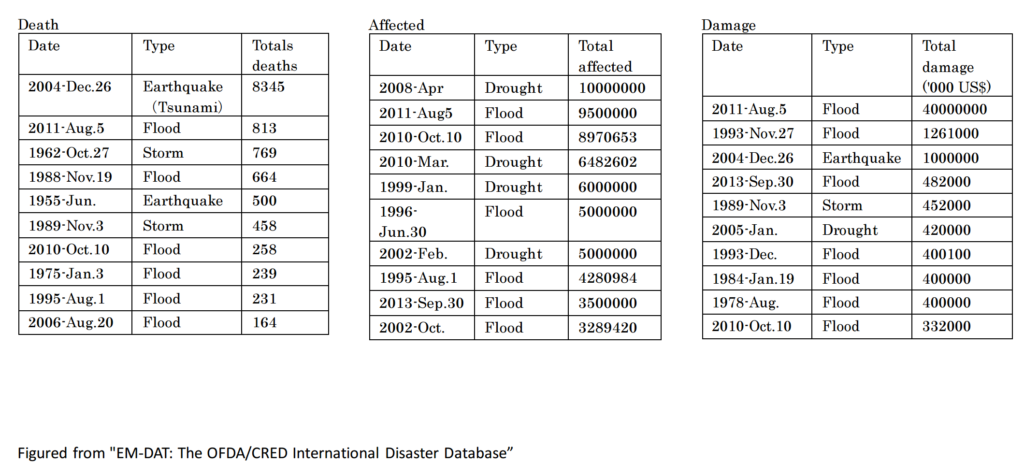

Table 1 Disaster data in Thailand

The EM-DAT database analysis covers disasters from 1900 to 2014. Notably, the most severe impacts—measuring deaths, affected populations, and economic damage—have occurred primarily since the 1970s. Two catastrophic events stand out in Thailand’s disaster history:

These events have dramatically shaped Thailand’s approach to disaster risk management.

Risk Assessment Mapping Framework

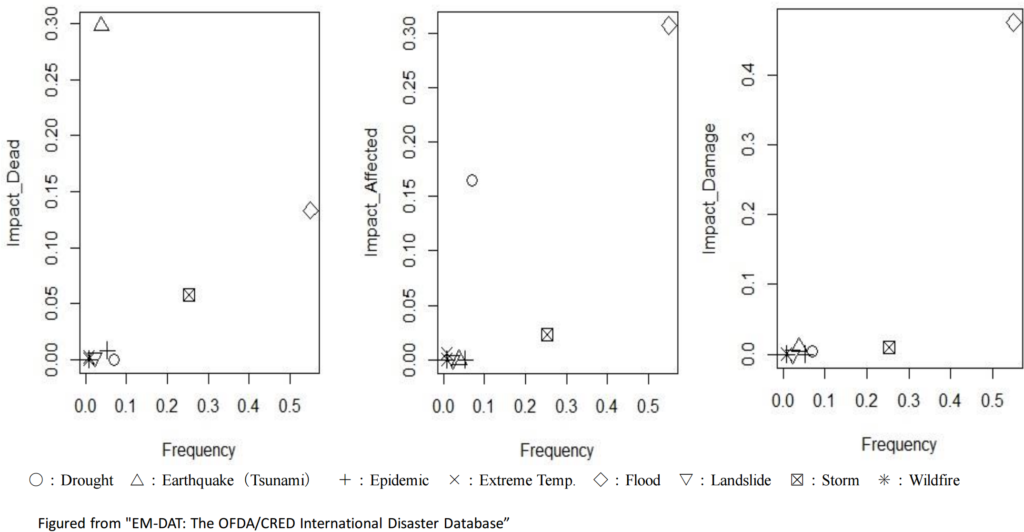

Figure 1 National Risk Assessment Mapping in Thailand

The above visualization presents Thailand’s risk assessment map created using EM-DAT data spanning 1900-2014. This frequency-impact analysis by damage type offers a straightforward yet comprehensive overview of Thailand’s disaster risk landscape.

Risk Evaluation Matrices

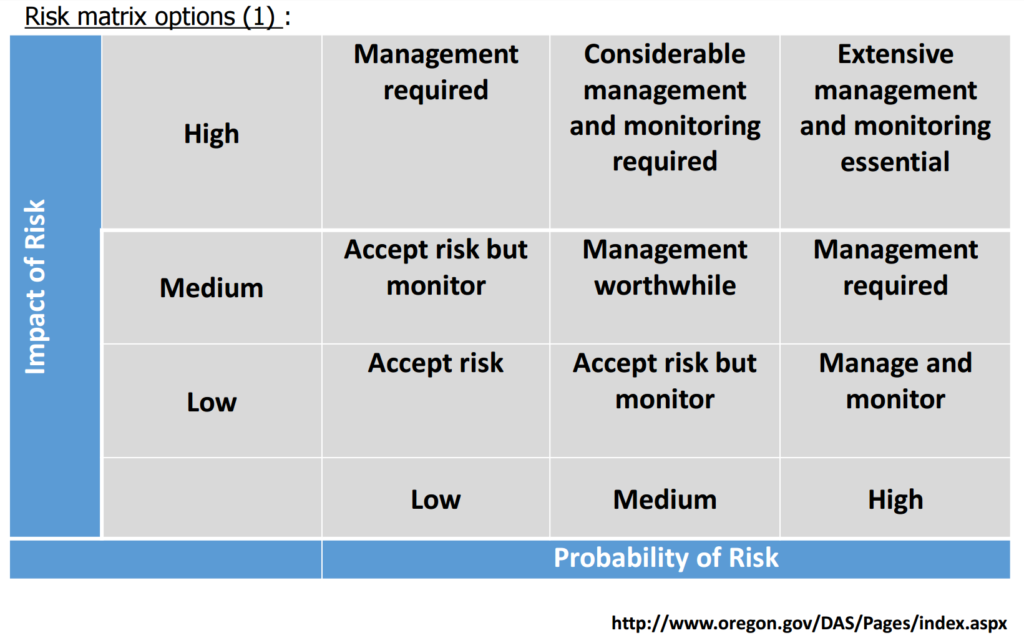

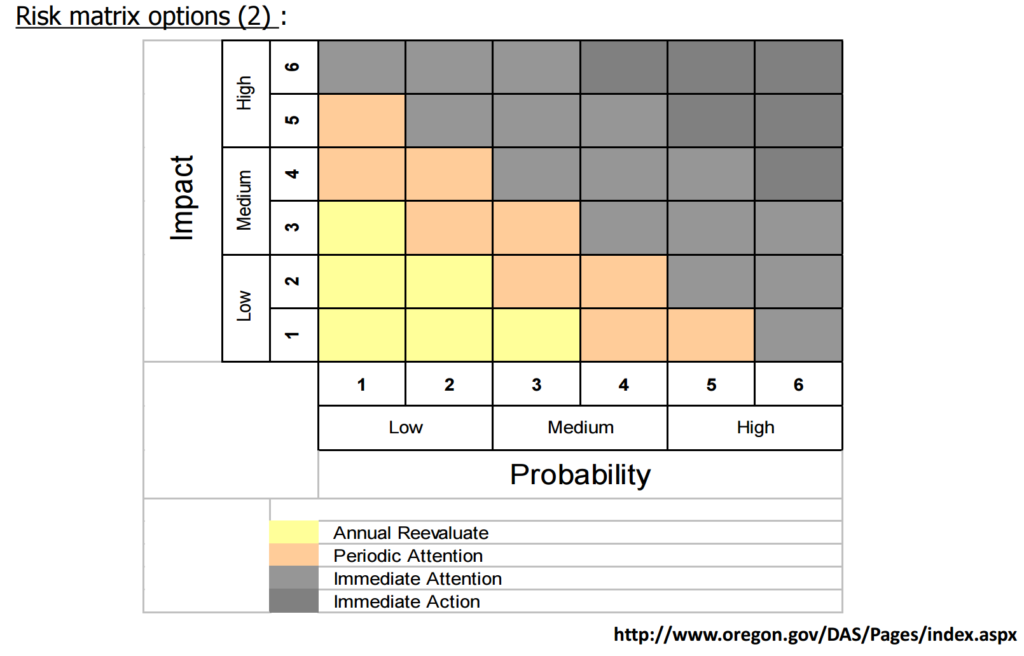

To properly contextualize these risks, we employ two complementary evaluation matrices:

Figure 2 Risk matrix options (1)

Figure 3 Risk matrix options (2)

Key Findings and Priorities

The risk assessment mapping (Figure 1) clearly identifies flooding as Thailand’s most critical disaster risk requiring immediate attention and resources. According to the evaluation matrices shown in Figures 2 and 3, flood events necessitate:

- Extensive management systems

- Comprehensive monitoring networks

- Immediate action planning and implementation

This preliminary analysis serves as a foundation for more detailed research. A report for the conference (Conference: 13th International Conference on Thai Studies) has published a more comprehensive examination of these findings.

Additional Resources

For more information on disaster risk reduction in Southeast Asia, visit the natural hazards research journal (open access) .

Day_209 : Snow Disasters: When Winter Wonderland Turns into a Nightmare

Winter’s beauty can turn dangerous with heavy snow, blizzards, and ice storms. These snow disasters cause power outages, transportation chaos, and property damage. But what causes them, and how can we prepare?

The Science of Snowstorms

Snow disasters happen when cold temperatures, precipitation, and wind combine. Think of heavy snowfall, icy roads, and massive snowdrifts. Climate change is making things worse with more intense snow and hazardous ice.

The Impact

Snow disasters disrupt transportation, causing accidents and delays. Power lines snap under the weight of snow, leading to blackouts. Buildings can even collapse, and ice dams cause leaks and damage.

Fighting Back: Snow Removal and Prevention

Traditional methods like shoveling and plowing are still essential. But we now have snowblowers, snowmelt systems, and de-icing techniques. Advanced weather prediction helps us prepare, and GPS-guided snowplows clear roads faster.

Be Prepared!

Even with the best technology, snowstorms can still hit hard. Have an emergency kit with food, water, blankets, and a first aid kit. Plan for transportation and communication in case of an emergency.

Stay safe and warm this winter!

# Image Source: Unsplash